2. Reserve Aviation

Regiment

— When fighting began in the Kuban, did you think that you

would be sent to fight?

All the graduates from our school were

sent there. But I was sent to the 4th ZAB (Zapasnaya Aviatsionnaya Brigada -

Reserve Aviation Brigade), which consisted of 11, 25, and 26 ZAPs (Zapasnoy

Aviapolk - Reserve Aviation Regiment). With time I served in all these

regiments. 26th ZAP was based at the Sandary station, near Tbilisi; 11th at

Kirovabad, and 25th at Kutaisi.

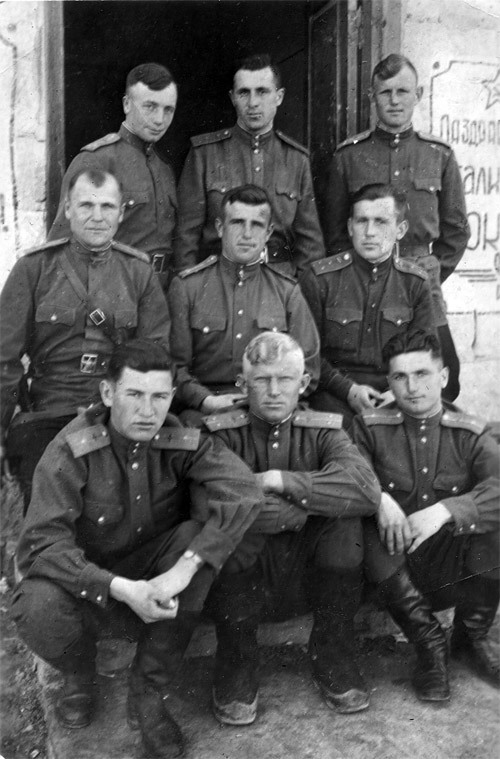

Kirovabad. 11 ZAP.

1-st row: Zabelin, Sharuyev, Tarasenko

2-nd row: Squadron engineer -, Squadron commander Fedorov, Squadron adjutant

-.

3-rd row: Flight commander Pekalov, Flight commander Didenko,Vorobec.

— What was the difference between a ZAP

and combat regiment?

There is a big difference. In combat

regiment pilots fly combat missions. Speaking of organizations? In both

regiments there was a regiment command, squadron command, political officer,

and navigator. The 11th ZAP was mixed, and consisted of two bomber squadrons

– one on Pe-2, another one on Bostons [A-20] and B-25s, and the 3rd squadron

was equipped with Cobras, Tomahawks and Kittyhawks. There also were some

UTI-4s. This squadron, under command of Fedorov, was stationed separately

from the rest of the regiment, at the airfield Kirovabad-West. American and

British fighters were flown here from Iran, and I was sent here after

finishing flight school in the summer of 1943. Later it was commanded by

Kondratyev. When I was sent to 25th ZAP, it consisted of only one squadron

and six instructors.

— How many pilots did you personally

train?

I trained 5–6 pilots simultaneously.

That’s those whom I had to teach and train for a long time. Maximum I had a

whole squadron – twelve men. That’s from a combat regiment. Pilots arrived

there with different capabilities, so I trained only those who needed it.

— What was the composition of the 26th

ZAP and what did you do there?

First of all, during the Kuban battles our

aviation suffered big losses. And especially LaGGs. When all LaGGs were

spent, pilots would return to the 26th ZAP. They received new planes there

and flew back to the front shortly afterwards. Their route was by the

Caucasian coast toward Sochi and Krasnodar.

— That is, you saw the same pilots more

then once?

Yes, several times. My friends, with whom

I graduated, now fought in the 805th IAP, if I remember correctly, invited

me to fight with them. I applied for a transfer, but it wasn’t allowed.

805th Tilzitskii,

order of Alexandr Nevskii fighter air regiment. In the active army:

• 05.07.42 - 09.12.42

• 19.07.43 - 10.05.44

• 13.10.44 - 09.05.45

Was formed in October 1941. Was equipped with LaGG-3 fighters. From May

1944 was transferred to La-5. During the war pilots from this regiment

shot down 88 enemy airplanes.

— What was the training procedure in

the ZAP? There are totally different recollections: some say that they

discussed tactics, others remember that they did nothing for several months.

Specifically at our regiment, there was no

serious training done. Regiments came to us to receive new planes and

pilots. After a brief period they would return to the front. There were no

group flights or shooting range practice. Nothing like this.

— Who organized the training? Were you

responsible, or IAP Commanders, or the ZAP Commander?

If an IAP commander came with the

regiment, then he was completely responsible for everything. I have to say

that after Evlakh school, I came to the 11th ZAP, which dealt with imported

airplanes. This mixed regiment was based at Kirovabad. Mainly its squadrons

flew on the Pe-2, but it also trained pilots to fly A-20 Bostons. This

airfield was packed with foreign airplanes. There must have been a thousand

of them: Cobras, Kittyhawks, Tomahawks, even Thunderbolts. There were very

few Thunderbolts, but they still were there. I was about to fly one of them;

I already had passed all the exams, but then I was sent to the 26th ZAP.

In the 11th ZAP we had to deal with different pilots. A portion of them was

from the combat regiments, and came along with their regiment commanders;

there was no problem with them. Another group consisted of those who began

to fly the U-2, for example, but later had no chance to complete their

training. Among my cadets was an HSU, who used to be a commando. He received

his title for hunting after officers–“tongues” [a “tongue” was a live

prisoner who could be interrogated for intelligence purposes]. He used to

tell us a lot of interesting things. He told me about his attitude:

— For me to kill a man is like killing a fly!

— Did you teach him to fly?

Yes, he graduated and was sent to fight,

but I lost track of him. I don’t even remember his name. Several men from

the Pokryshkin division were my graduates. I used to be there – I ferried

Cobras to them from Kirovabad. There was a special regiment that ferried

planes from Abadan to Kirovabad, the same like there was a regiment that

flew at Chukotka… Recently there was a film made–“Peregon.” Have you seen

it? It’s a hallucination of a pale mare under a bright moon! Starting from

the point that no American girl ever flew to us on a ferry flight. This film

is complete rubbish.

We ferried planes to Pokryshkin’s division, more then 20 planes in all. As

we landed, pilots started to argue who will get which plane.

11 ZAP

Kondratyev, Levashov, Vorobec

On the wing: Sobolev, Tarasenko, Sulemenko, -, Zabelin, -, -, Pekalov -, -,

— How did you like the American planes?

Cobras indisputedly were superior to

Kittyhawks and Tomahawks.

— A pilot from 103rd Guards Regiment

told us that their pilots had no problems when they flew Kittyhawks, but

when they switched to Cobras, in a very short period of time they lost five

or six pilots, which was more than their combat losses for the same period!

Yes, it could be. The Cobra was unusual.

The main defeciency of this plane was that it stalled easily and its curse

was to spin. If it enterd one it could be unable to recover. I knew a lot of

pilots who died this way… (4th ZAB lost no less than 22 pilots killed after

transfer to the P-39. I. Zhidov)

But my attitude toward this was rather reckless, and when I began to fly the

Cobra, I started to gain altitude without permission and execute spins. It

was quite easy for me, and I recovered without any problems. So I told my

Squadron Commander that I was not afraid of the spins.

All pilots were assembled on the airfield, and I was ordered to start

spinning above the airfield. I gained about five thousand meters above

ground, and as usual entered the spin. I started recovering, but to my

surprise it did not even start to respond. I must have made about fifteen

revolutions, and whatever I did – it did not recover. By this time I was in

the area of the village Khvanchkara – there is a wine named after this

village. There is a deep valley, and this valley saved me – it gave me a bit

of extra space, as I recovered well below airfield level. I must have had a

rather frightened appearance. And I decided that under no condition would I

do anything like this again!

11 ZAP:

Kondratyev, Levashov, Vorobec

2-nd row: -, -, Sobolev, Zabelin, Sulemenko, -, Tarasenko, Zinovyev, Pekalov

— Could you compare the Cobra with the

Yak or LaGG?

There is no sense in comparing the Cobra

with the LaGG, because it was vastly superior. There is no sense to compare

the Yak-3 with the Cobra for the same reason. But all other Yaks were worse

than the Cobra. First of all it had a better view, radio equipment, and

speed. It had armored rear glass that provided good view to the rear, while

our planes’ metal head rests did not allow our pilots to look behind them.

— The Cobras that you ferried had what

kind of weapon arrangement? Did they have wing machine guns?

First of all, 37mm cannon. Two 12,7mm

machine guns in the nose. And I don’t remember exactly, one or two heavy

machine guns in the wings—one in each wing, if I remember correctly.

— Was there a difference between the

Kittyhawk and Tomahawk?

They had little difference, and at first

we did not even understand which one had arrived. There was no special

course of training for them, and they even had a similar weapon arrangement.

I know that Navy pilots liked this plane and were satisfied by its

characteristics. It had greater fuel capacity than Cobras had, and it came

equipped with a huge drop tank. Its engine worked very smoothly, and it had

a greater life expectancy, like most other American engines.

— Cobras had the same engines as

Kittyhawks. But most pilots complained that if you flew like was prescribed

by the book it would work for 500 hours, but if you flew like you have to in

combat it would burn out in 100 hours.

Yes, that’s right. On the Cobra the engine

was behind the pilot, and a large drive shaft went throught the cockpit to

the propeller right between the pilot’s legs. Sometimes, but not always, you

felt a vibration. On Kittyhawks the engine worked so smoothly that you could

fell asleep...

— Were there cases when Cobra tails

were broken in a high-G maneuver?

Yes, there were such cases. We complained

to the United States and they soon sorted things out and strengthened the

tails.

— Here is a question. Did these

airplanes have piss tubes?

On American planes there were, even on

fighters. I even “tested” it.

— Did you fly to the firing range in

Cobras and Hawks?

Of course. In the 11th Regiment I flew a

lot, and shot from the Cobra and other planes.

When you shoot the 37mm cannon, you can count every round fired. It was a

very slow firing weapon. And it felt like the plane was stopping for a

moment.

11 ZAP. Kondrat'ev, -,

Sobolev, Zabelin

— When you fired a wing-mounted machine

gun, did it cause problems?

No, no problems. But you could see the

tracers and it looked like a firework.

— Did you experience any national

problems in Georgia and Kirovabad?

Yes, we did. For example, a road from the

airfield to Kirovabad went through a vineyard for four kilometers. During

the day time it was quiet, but at night it became dangerous for us.

Once, when I fired at the shooting range with my TT, its firing pin broke.

My pistol was exchanged for a Nagant revolver. I used to wrap it in a piece

of cloth and carry it in my pocket. Once, I was returning at night from the

airfield, and two Azeris jumped out of the grape vines in front of me, and

started shouting at me something like “Stop!” I pulled out my Nagant and

said:

— I’ll kill both of you right here!

Those cowardly jackals disappeared. When I got home and looked at my weapon,

I found out that I had lost its firing pin. In other words, I was completely

unarmed! From that moment on I became more careful.

— And what about Georgia?

It also happened there. For example in

Kutaisi. There were very few Georgians not only in aviation, but in the

ground forces also. Later there were a lot of films about the “brotherhood

of nations”: “Soldiers father” and others. Many men avoided induction in

Georgia. There was a lot of draft dodging in the draft-age cohort there. We

were young, and we used to go from time to time to the local dancing arena.

Not too often, but we still sometimes did. There were a lot of young

Georgians there. They attacked us when we were leaving the dances.

Once I was a participant in such an episode: dancing arena, noise, and

shouting. I saw that our cadets were leaving, and behind them a crowd of

Georgians at least three times as large made their way out. They were going

to “teach those Russians.” Their only method of education was the knife and:

“I’m gonna cut your throat!” So I decided to go home as well. At first we

were walking, then we started walking faster… Eventually we were running,

and Georgians chased us. Among our group was a cadet, Velichko, who managed

to somehow arm himself with a flare pistol – sidearms were not allowed to be

issued to the cadets. He began to fire flares in front of our chasers. The

suituation was getting rather grim, so I pulled out my pistol and started to

fire above their heads. There was a croud of over 100 Georgians by now, but

they became frightened and stopped. Not stopped, but followed us at a great

distance, as we walked toward the bridge over the Rion River. The river

wasn’t too deep, but the bridge was quite high, and if they would have

caught us there it was a long flight down. When I had almost stepped to the

other side of the bridge, which was “our” territory, a Georgian appeared

with a huge knife and tried to stab me. When I saw a knife pointed at me, I

shot. The attacker fell to the ground and started begging me not to kill

him, saying that he did not mean to stab me, that it was all the fault of

another man, and that he would never do it again. Thus, with fire we crossed

the bridge. It also shows the Georgian mentality – they are eager to attack

anybody who they think is weaker, but if there will be a response, they will

always keep assaulting you by words, avoiding real fight as long as

possible. Every single Georgian is a good man on his own, but as a crowd

they are mad and uncontrollable.

Yes, there were cases like this. These events became known to Georgian

authorities, but they listened only to their side and made complaints to our

high command in Tbilisi.

— During the GPW, attacking a Red Army

officer meant court martial to the attacker and up to execution as the

penalty. Did your attacker survive?

In any case, I shot above his head, so if

he died, it must have been death from fear, not of wounds.

— Were there any subsequent problems to

you?

No. We just stopped going to the dances.

— Back to the national question. What

was the attitude toward Jews? There are different opinions about them.

There were almost no Jews in Georgia and

in the Caucasus region. They were present in aviation, but not too much. I

had a brief chance to see them in real life, but I think that all

generalizations on nationality are incorrect. For example, when I served in

Primorye, in the 821st Regiment, there was a pilot Dmitriy Blankman. He was

short, but he always looked to be ready to fight. In those days there were a

lot of Jews among doctors, and our dentist always claimed that Dmitriy

Blankman was the best pilot of our regiment.

But Dmitriy was a poor pilot. He hardly could fly the Cobra and he did not

master the MiG-15 at all. Later he was discharged from aviation, which

caused grumbling among our garrison Jews that he was removed because he was

of a certain nationality.

Another Jewish pilot I saw was the navigator of the 256th IAP, Major

Kolmanson, Viktor Emmanuilovich. He fought in Korea, and fought well. I saw

how he was killed. (Major Kolmanson Viktor Emmanuilovich was killed on

20.05.1952. Buried in Port Arthur (nowadays - Lyuishun), China. I. Seidov).

When we returned to our base with empty tanks and were coming in for

landing, Sabres would come and attack us on final approach right above our

airfield. They tried to shoot us both on landing and on takeoff. And more

than once I had to make sharp turns right after take off at an altitude of

2–3 meters. Our flight control would call over the radio:

“A pair of Sabres is diving on you!”

And I had to turn as sharp as possible, almost catching the ground with a

wing, so that the first burst would not hit me. Kolmanson came home with

empty tanks from a fight, and was on final approach. He was leveling off and

almost touched the runway. At this moment a pilot is completely defenseless.

And suddenly, a long burst from six heavy machine guns from a Sabre at point

blank range. His airplane caught fire, half rolled, and fell to the ground.

That’s how this pilot’s fate ended…

— Let’s return to the GPW.

I spent slightly over one year in the 11th

ZAP. In July 1944 I was transferred from the 11th ZAP to the 26th.

— What was the reason for your

transfer?

I was included in a special group to

execute an unusual mission. Up until 1944 the aviation plant had produced

LaGGs, and later they started building the Yak-3. I flew the first Yak-3.

This plane felt like a toy to me. It really was another airplane, different

flying, different state of mind to the pilot, if you will.

Perhaps you know that the first one who began collecting money for new

airplanes was Ferapont Golovatyy. The first plane built on the money

collected by Golovatyy was presented to Yeremin. By the way, I met him in

person, and he was my direct chief here, in Leningrad. When it became clear

who was winning, Georgian authorities asked comrade Stalin: They wanted to

build airplanes on the money raised from the Georgian people. Money was also

collected from military units stationed in Georgia; we also gave money for

this cause.

Kutaisi. 25 ZAP.

-, Vorobec, Zabelin, Tarasenko, Zinovyev, -, -.

2-nd raw: Pekalov, Kondratyev, Levashov, –, Sulimenko.

— How many “gifted” planes there were

and what did they look like?

There were four “gifted” planes. Airplanes

had gray–gray camouflage pattern, and from the nose to the tail there was an

insignia in large red letters: “For the Motherland! [Za rodinu],” “For

Stalin! [Za Stalina],” “Forward to the West! [Vpered na zapad],” and “For

Victory! [Za pobedu]”

— From all of Georgia – four planes?

Yes. Georgia bought four Yak-3 planes from

Tbilisi aviation plant. A letter appeared to send these planes to combat

pilots, so that they would fly them in combat. I was included in this group

of pilots, which was arranged in the 26th ZAP because I already had flying

experience with the new plane. We pilots had no idea about what had been

arranged. It turned into a huge show. The first planes built at Tbilisi were

sent to us; we flew them, trained in group flying, and several times we had

to fly show flights. Finally we said that we were ready, and a date was set

for our departure. On the night before our departure, insignias appeared on

our planes, and on the day of departure there was a huge celebration, where

all the Georgian leadership was present.

— Were these “gifted” planes in any way

different than other Yak-3s?

No, there was no difference. We flew on

these Yaks to Poland. The Yak-3 had low fuel capacity, less then other Yaks

and LaGGs. Because of this we had to make eleven intermediate stops.

It took us several days to arrive at our destination point. We were led by

two B-25 “Mitchells,” which also carried spares and our mechanics.

Our flight was tracked up until our landing in Poland. Quite often there

were problems with fuel supply, and it was common that ferry crews had to

wait for several days. But we had a “green wave” – all our problems were

solved by the call from Moscow. It surprised us from our first landing in

Baku. We landed, and we were immedieatelly informed that there was no fuel

for us. People who were flying with us called to Moscow, and fuel appeared

in about ten minutes.

— Did you fly on economic mode?

Yes, of course, but the route was

calculated by the Mitchell navigators and they were responsible for our

arrival.

— What do you think about the radios on

the Yak-3?

Well, it might be was worse than American

radios, and there was more squelching, and effective range was lower, but it

still was a leap forward from the old radios. Radio communications became

more stable. But what was more important – these were completely different

planes. Yak-3s even then were called a “weapon of victory.”

We flew and flew. Everything seemed to be fine. When we came to Zhitomir,

which at that time became a node for ferry flights, a tire had burst on my

plane on taxiing. It was a major problem – we were the first Yak-3s to

arrive there and there were no spare parts on the airfield. Yak-3s had a

smaller tire than on any other airplane.

We were fed, and then we started looking where we could stay for the night.

The entire airfield town was in ruins. The only remaining brick building was

occupied by a women’s fighter regiment assigned to PVO. I didn’t even know

about such female regiments. It turned out that there was only one male –

the instructor, who was responsible for flight training. They were dressed

in trousers, very clean. We found some hay in the ruins and slept there. We

woke up in the morning and went to the canteen. Before we departed from

Georgia we were dressed in all clean and new stuff, and now we were covered

in hay.

The female pilots saw us and started laughing. But when we came to our

planes, and they understood that we were also pilots, not technicians or

mechanics, they started envying us – their regiment was equipped with

Yak-7s. Boris Fadeev was our flight commander, and he said:

— I’ll exchange one of our planes for your full squadron equipped with

pilots.

While we were talking, our technicians disassembled a wheel from a LaGG and

somehow managed to stick a camera into the Yak’s tire.

Anyhow, we arrived at our destination point. We landed at the airfield that

was built just in a few kilometers away from the front line, near Sandomir.

The river wasn’t crossed yet, but fighting had been going on for a rather

long period of time. This airfield was occupied by the regiment where Boris

Yeremin flew. It was an ordinary grass field, just 15 kilometers away from

German lines. The Yak-3 had a short supply of fuel, so we had to fly from

this airfield, but it had to be done in such way as not to give our position

away.

That’s how we ended up in the 91st IAP as probationary pilots of a reserve

aviation regiment. This was a common practice during the war. They sent

instructor pilots to combat units for a period of two to three months. We

arrived in August, and until December we kept asking the regiment commander

to leave us in the IAP. We did not know about it, but there were long

discussions between the regiment commander and higher levels of command. And

once we were told:

— You will stay with us!

Our spirits were raised – we had run away to the front! There were cases

when instructors ran away to the front.